Sonia’s Book, MA BIBLIOTHÈQUE 2025.

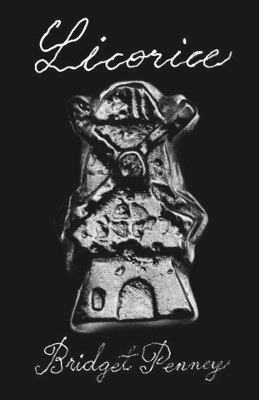

Licorice, Book Works 2020.

Richard Marshall reviews Licorice

‘Penney turns you around and around constantly, as if you’re on the windmill’s sails, so that you can’t pin down the source of that unease. Which is what every great horror does. This is a particularly classy example. It doesn’t ever reveal itself in full. It doesn’t nail itself down. So it keeps itself alive right up to the very end and then further. It’s one of those disturbing tales that can be read again and again. There’s no final reveal that shares the code, so to speak. I loved it.’

Anna Aslanyan reviews Licorice in the TLS, August 2020

‘Licorice, a novel by Bridget Penney published by the arts organization Book Works, is certainly full of experimental quirks, such as sparse punctuation and unattributed chunks of dialogue. Played out in the space of a hundred-odd uncluttered pages, these features allow the unconventional narrative to get closer to its core themes: sex, immigration, the environment, property and, above all, violence. There is, however, also a plot, which centres on the story of Nan Kemp, a Sussex woman who, according to a fourteenth-century folk tale, killed her children and fed them to her husband.’

Jamie Sutcliffe reviews Licorice in Art Monthly no. 440, October 2020

‘Bridget Penney’s Licorice is a darkly curious novelistic confrontation with a substratum of horror cinema commonly known by its ambiguous prefix, “folk”. In Penney’s own words, the book forms an attempt to “write radically in an inherently conservative genre”, and the result is both a peculiarly enjoyable work of tale-telling and a dissonant and disquietingly timely artist’s book that channels the reality-checking character of slipstream fiction into a cautionary parable….Often reading like a lost Mike Leigh script re-penned with the deft conversational dynamism of American novelist Barry Gifford, Licorice brilliantly foregrounds its folk through chaotic streams of spoken and internal dialogue, its characters haunted by a tale as apocryphal as the Englishness within which it is steeped.’

Tony Messenger reviews Licorice on Messenger’s Booker (and more), October 2020

‘Off-kilter, yes but when your “surroundings are brand new and strange you should treat everything as a gift rather than a threat” … Approach the novel with this philosophy in mind and there are riches galore, yes it’s not all comfortable, however persistence will bring forth a number of horror movie tropes, if you’ve watched English horror you find yourself entering into a dream like state, déjà vu as you are sure you’ve come across this scene before.’

Matthew Parkin writes about queerness and rurality with a nod to Licorice in MAP Magazine, May 2020

‘The windmill in Bridget’s narrative is a device to hear a past, adding the same authenticity to the film production as hand dyed burlap wardrobes and the real life sexual relationship between the actors. I guess what I am trying to clumsily gesture at here is the distinction between the real and simulated sex, landscape, narrative.’

Close-up of Boerderij, ‘Farm-shaped Dutch Salty Liquorice’. As served at the launch for Licorice at the Horse Hospital, London on 27/02/2020.

Photo by Tamar Shlaim.

Index, Book Works 2008, second edition 2015.

Richard Marshall reviews Index in 3:AM Magazine, July 2008

‘Her voice in the novel is weird, neither actual nor under done. It is a style that winks towards authority whilst at the same time has a stab at the phenomenological oceanic…. it reaches towards an anti-picturesque in a way remarkable for its hesitant and perhaps coy aesthetic purity’

Charles Danby reviews Index in Tate Magazine, December 2011

‘Here, through Bridget Penney’s book, Index the experimental ethos posited by Berman reaches a further site of contemporary operation. Essentially a work of fiction, Penney’s book is structural as much as it is narrative, divided by variations of prose, and intercut with passages of compositional typography, it circumvents clear-cut categorisation. At the centre of the book are the fictional characters Roland and Julie. Their construct shifts from chapter to chapter, not through the generative psychosis redolent of Ballard’s protagonist Travers in The Atrocity Exhibition 1970, but through an imploded chronology of historical timeframe.’

Sally O’Reilly reviews Index in Frieze 116, June 2008

‘Bridget Penney’s Index (2008) also demonstrates this anti-literary strategy. Here the orthodox narrative arc is utterly splintered and reconfigured, and lyrically wrought vignettes of historical and fictional episodes are held enigmatically apart rather than enmeshed. Much of the historical material relates to 18th-century sources and the unknowable interiority of figures and events in an age of reason and revolution. The inference of an ultimately scrambled and therefore failed index emphasizes the hubris of taxonomy and genre…’

Honeymoon with death and other stories, Polygon 1991.

Shortlisted for Saltire Society Scottish First Book of the Year 1992 and PEN/Macmillan Silver Pen Award 1992.